Extreme weather is the new norm, and the science of forecasting is rapidly evolving to meet the challenges. Stacy Mohan looks at how NIWA researchers are joining forces to predict the impacts of extreme events, so communities can better prepare for their future.

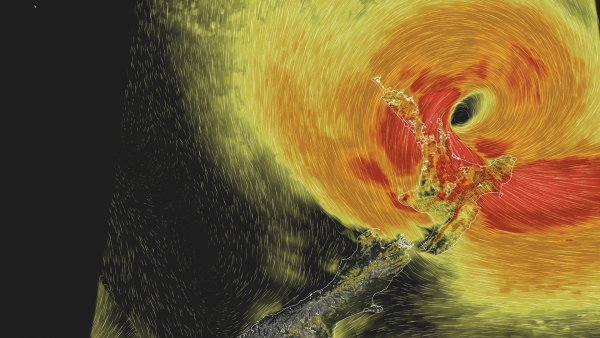

Cyclone Gabrielle swept into Hawke’s Bay and Tairāwhiti in the second week of February, unleashing torrential rain and record floods.

Less than 10 months later, farmers and orchardists hit by that deluge are now facing the prospect of a summer with too little rain.

Rapidly warming ocean temperatures in the mid-Pacific have resulted in one of the strongest El Niño weather patterns seen in recent decades.

For those in Hawke’s Bay and Tairāwhiti, the westerlies look set to be stronger for longer this summer, likely bringing extended dry spells and potential water shortages.

It is an unwelcome reminder of the realities of living in a highly variable and changing climate.

Predicting impact

New Zealanders are fast realising that climate change means living with an increased risk of climate extremes. The same climate drivers that are powering up El Niño, have prompted warnings of a higher risk of tropical cyclones in the Pacific Islands this summer and could also bring flooding to Fiordland and the West Coast.

NIWA forecasting, climate change, hydrology and natural hazards researchers already work on a whole raft of programmes dealing with the challenges of climate change. However, in recognition of the devastation storms like Gabrielle deliver, NIWA has prioritised further resource into predicting what extreme weather events will actually mean for affected communities.

Chief Executive John Morgan has announced an additional $5 million a year for a package of projects focused on the impacts of extreme weather events (see NIWA boosts extreme weather research below).

Cyclone Gabrielle clearly demonstrated that advanced supercomputers and weather modelling mean NIWA forecasters can already accurately predict the arrival of storm systems, along with the rainfall totals and wind strengths they will deliver.

The focus now is on improving the forecasting of how those rainfall figures and wind strengths will interact on the ground for communities, environments and ecosystems in the line of fire.

The new funding will enable NIWA scientists to investigate new ways of predicting the potential impact of a combination of storm outcomes, such as floodwater, slips or coastal surges, to help communities prepare for hazards peculiar to their region.

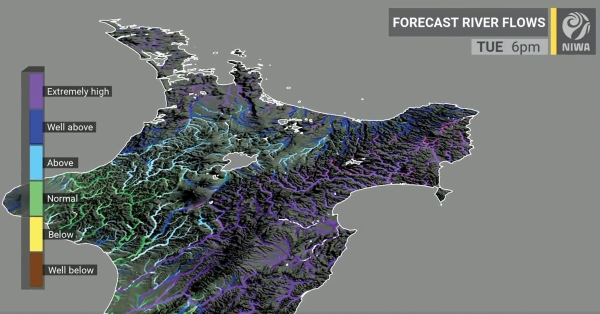

NIWA climate scientist Nava Fedaeff is spearheading one such project. The research pulls together the skills of NIWA’s climate, meteorology, hydrology, data science and hazard specialists, combining five-days-ahead ensemble weather forecasting, river flow predictions and inundation mapping.

The team are producing models to detail – down to street level – people, property or infrastructure at risk when storms strike.

Fedaeff stresses the importance of early warning. "The two to five-day window is a critical timeframe for taking proactive measures,” she says.

Ensemble forecasting is a method used in numerical weather prediction to look at possible outcomes. Instead of making a single forecast of the most likely weather, forecasters run several computer models at a time, each under slightly different scenarios. This set of forecasts indicates a range of future weather conditions. Where these scenarios converge on a particular outcome, forecasts can be issued with greater confidence.

In this new project, Fedaeff and team are linking weather ensembles with river flow modelling, to show where flows could be highest under different scenarios. And then taking this a step further to link with inundation mapping.

“What people really want to know is not just whether the river is running high, but what areas will be flooded, and what’s at risk from that potential flooding,” says Fedaeff.

“We’re exploring the potential of artificial intelligence to enable us to move from weather forecasts to inundation forecasts, quickly enough to get useful information out to those who need it.”

Taking the project beyond forecasting and into predicting impacts also involves the use of RiskScape – a software tool that enables risk and vulnerability analyses of multiple hazards. It is a tool that was developed by NIWA and GNS Science, alongside more recent partner Toka Tū Ake EQC and collaborator Catalyst IT.

Initially the project will focus on mitigating the risks associated with river flooding, but the intention is to look at the impacts of other weather-related hazards – such as marine heatwaves, coastal storm surges, droughts or wildfires.

Drought forecasting

The flood forecast project complements other NIWA work already underway in relation to extreme weather events.

This year’s El Niño is coupled with another pronounced southern hemisphere climate driver, a positive Indian Ocean Dipole. This last occurred in 2019. The result was record-setting dry spells in the north and east of the North Island and a water crisis for Auckland City. The water supply issues alone cost Auckland ratepayers more than $200 million.

NIWA meteorologist Ben Noll says his team has already been briefing key agencies and authorities in drought or fire risk areas about the threats El Niño may deliver in the months ahead.

“Along with reduced rainfall, strong westerly winds are expected to be a theme for several regions throughout summer and possibly into autumn,” explains Noll.

“NIWA’s role last summer in providing wind and rain forecasts to councils and emergency managers has now swung to include regular information briefings for the agricultural and horticultural sectors.”

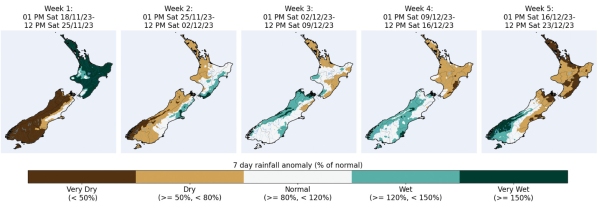

NIWA has provided New Zealand with seasonal rainfall and dryness predictions for more than 20 years, steadily increasing the accuracy, resolution and time length of these forecasts. The latest version uses climate modelling and data-driven techniques to deliver district-level dryness predictions up to five weeks out. Called the Drought Dashboard, it was launched earlier this year by NIWA and the Ministry for Primary Industries.

“The Drought Dashboard is part of the NIWA35 platform, which is marrying artificial intelligence with physical science to make high resolution, sub-seasonal climate predictions up to 35 days ahead,” explains Noll.

NIWA35 is based on input data from a model issued daily by the US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NIWA uses this data and enhances its accuracy and precision over New Zealand using data-driven techniques.

The improved model better captures the climatic variability that occurs across the country’s complex terrain.

“The tool updates daily to provide forecasts at a much higher spatial resolution than previously available.

“It enables district-level predictions of dryness and drought, and helps farmers and growers to better prepare,” says Noll.

NIWA35 shows the power of turning weather and climate data into accessible tools that communities can use to prepare for what the climate is now throwing at them.

Elsewhere, NIWA scientists are working with research colleagues on a wide range of similar projects. These include using new data techniques to predict what extreme rainfall may mean at a catchment level for subsidence risk, and mapping the combined impact of rising sea levels and storm surges. With further storms and droughts on the horizon, demand for applied climate science and impact forecasting will only grow.

NIWA boosts extreme weather research

Almost half of NIWA’s new $5 million per year package for extreme weather-related research will go to improved forecasting of the impacts of extreme weather.

Funds will also go to supporting the development of climate change resilient infrastructure and working with iwi/hapū and Māori business on climate adaptation.

“We know that such extreme events are going to become more frequent and more intense, and we need to be better prepared,” says NIWA Chief Executive John Morgan.

“Advanced, high-precision forecasts that link different hazards will help all New Zealanders – including iwi, emergency managers, government, councils and the public."

This story forms part of Water and Atmosphere - November 2023, read more stories from this series