It’s just after 4am and the Sanford fish-processing shed on Auckland’s Viaduct Basin is a riot of activity.

Hundreds of snapper, fresh off the boat, are coming down the line. Skilled filleters make short work of the cuts for restaurant tables or supermarket chillers. Whole fish are readied for export.

Two NIWA researchers, Rikki Taylor and Dr Darren Parsons, are also hard at work on the line, sampling for science.

Fisheries New Zealand (FNZ) is the government agency that manages the sustainability of our fisheries. It does this by determining the dynamics of individual fish populations and deciding how many fish recreational anglers and commercial operators can catch.

This requires data – lots and lots of data, about a range of factors including age, sex and the growth rates of target species. Fisheries scientists use this data to produce detailed models of the health of regional populations and it is these models that guide the FNZ decisions underpinning sustainable fisheries.

NIWA has been providing independent fisheries science to FNZ since the 1980s. Much of the data driving this work is gathered at sea during targeted research surveys carried out by NIWA’s research vessels, Tangaroa and Kaharoa.

But the thousands of fish prepared for market every day in processing sheds across the country also provide much additional data.

Down on the Viaduct processing line, Taylor and Parsons are carefully working their way through a randomly selected sample of the catch, measuring each fish and then meticulously removing their tiny ear bones for detailed investigation.

“The boats that are coming in are part of our sampling lens,” says marine ecologist Parsons.

“They are going out there fishing and they see what is happening first hand. We are in partnership, piggy backing along to get a good view of what is happening in the water right now.”

Later, back in one of NIWA’s Auckland laboratories, fisheries modelling technician Helena Armiger puts those ear bones under the spotlight.

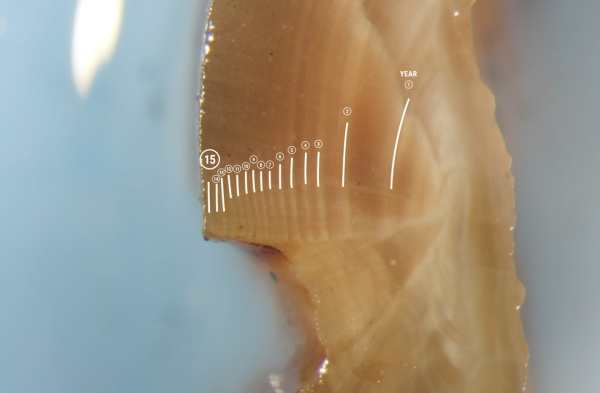

Like trees, fish produce annual growth rings. These rings are most pronounced in their ear bone – or to give them their scientific name, the otolith. Using her microscope, Armiger can carefully count the individual rings and work out a range of factors, including the exact age of each fish.

It takes about 10 minutes to age one otolith. Examine a large enough sample from each catch and you start to build a picture of the age structure and the health of the target fishery.

In the last year alone, in processing sheds from Leigh to Bluff, NIWA researchers extracted over 17,000 ear bones, from key species like snapper, tarakihi, trevally and blue cod.

“We don’t let an otolith go until two readers agree on an age, so we can give the best possible information to FNZ,” says Armiger.

If you know how many fish you are catching and how the age structure of your fish population changes over time, you can track the sustainability of your fishery. Lots of young fish, for example, is a sign of strong recruitment and a growing population.

Combine the information gathered from the otoliths, with other data sources such as biomass estimates from standardised research surveys or catch rates from commercial operations, and fisheries modellers can build a detailed picture of the health of specific fish populations.

“Obtaining information on the age structure of the commercial fishery is crucial to successful stock assessments,” says Marc Griffiths, Principal Science Advisor with FNZ.

“If a stock is doing well and it is above its target, we can increase the catch. If the stock is down below the target, we can cut back and rebuild the stock.”

Rikki Taylor doesn’t mind the early starts.

“We measure one fish here today, that will be one line of data. But this builds into a huge data set for Fisheries New Zealand.”

She also knows the difference that data will make.

“When you or I go out fishing on the weekend, I know there are going to be fish.”

This story forms part of Water and Atmosphere - May 2022, read more stories from this series.