A key habitat under pressure. The extent of NZ’s seagrass meadows has declined substantially in the last 50 years. This has been most evident in estuaries strongly affected by human activities. This is a trend that is evident globally.

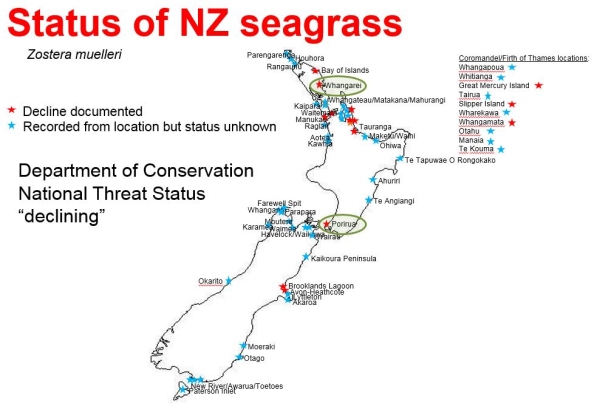

Consequently, New Zealand’s sole seagrass species (Zostera muelleri) has a National Threat Status of “At Risk – Declining”.

Why do we care?

Well, there are a lot of reasons to value these vast underwater meadows. Here are some key ones, they:

- Are rated the 3rd most valuable ecosystem globally

- Occupy 0.1% of seafloor but store 12% of ocean carbon

- Trap and transform nutrients (1 ha absorbs 1.2 kg N per year)

- Pump oxygen into water & sediments (1 m2 releases 10L per day)

- Stabilise the seabed with an extensive network of roots & rhizomes

- Are a foraging and feeding ground and refuge for marine life

- Contribute to biodiversity by being the only marine flowering plant

Some good news

Seagrass meadows can be restored and NZ has a local example to prove it. Whangarei Harbour lost almost all of its 1400 hectares of seagrass meadows in the late 1960s. A combination of human activities were responsible, with sediment pollution playing a key role. When certain activities ceased in the 1980s it appears that the slow road to recovery began. By the early 2000s it seemed that some expansion of remnant pockets might be occurring so work to assess the feasibility of restoration commenced. This led to transplant trials in 2008 and 2012, both successful and showing that this species can be transplanted with relative ease. Interestingly, widespread regeneration of seagrass in this harbour began in earnest in 2009 coincident with the first trial. Since then there has been steady recovery so that seagrass now occupies about 40% of its original extent. We are hopeful that the seagrass will continue to spread and reoccupy its full former range. Further transplants could be used to speed up this process.

But we don’t have all the answers just yet

Further south in Porirua Harbour, seagrass loss has also been a matter of concern to locals. Here, about 40% was lost in the 1980s, in particular from a large area at the head of Pauatahanui Inlet. Again, sediment pollution was a likely culprit. In 2015 a few transplants were placed at the head of the Inlet, but sadly they have not survived. The result was not unexpected because there was no evidence of reduced pollution. Nevertheless, the exercise has been helpful, with monitoring indicating that sediment biogeochemistry and accretion or accumulation rates probably control seagrass persistence more strongly than light climate. This is contrary to popular opinion and highlights the need for future restoration efforts to focus on more than just a favourable light climate to succeed.

So what more are we doing to advance our understanding of this?

NIWA’s “Managing Mud” programme is now undertaking research to identify the broader sediment-effect thresholds needed to ensure the long-term persistence of healthy seagrass meadows. Our research, in collaboration with Waikato University, will address the complex and multi-faceted effects of sediment pollution on the seagrass growing environment. Ultimately, we will incorporate these thresholds into source-to-sea hydrodynamic models to enable robust determination of the sediment loading rates, within receiving environment, that will provide for the protection and restoration of seagrass meadows in our estuaries.

Further information

Matheson, F.E., Reed, J., Dos Santos, V.M., Cummings, V., Mackay, G. (2017). Seagrass rehabilitation: successful transplants and evaluation of methods at different spatial scales. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 51: 96-109.

Matheson, F. Seagrass transplants contribute to regenerating seagrass in Whangarei Harbour, New Zealand. http://seagrassrestoration.net/zostera-restoration-in-nz.

More articles: Freshwater Update 75, November 2017