A team of NIWA scientists, students and representatives from Fisheries NZ spent 6 days in the Cook Strait carrying out experimental work on hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae) to better understand their biology and improve abundance indices.

Voyage leader Richard O’Driscoll explains the voyage represented a unique opportunity:

“Most of the time we go to sea we are ‘counting fish’ to monitor changes in fish abundance. This voyage gave us the chance to explore some of our knowledge gaps about hoki”.

Hoki is New Zealand's largest finfish fishery. The total allowable commercial catch was reduced from 150 000 t in 2018–19 to 115 000 t in October 2019. Spawning occurs between June and September, with the major spawning areas on the west coast of the South Island, and in Cook Strait. Dr O’Driscoll says “Having the hoki spawning in our ‘backyard’ – just a few kilometres from Wellington, meant that we could cram a lot of cool science into a short trip”.

One of the voyage objectives was to collect information on hoki eggs. Fisheries scientist Jennifer Devine is excited about the data that has been collected:

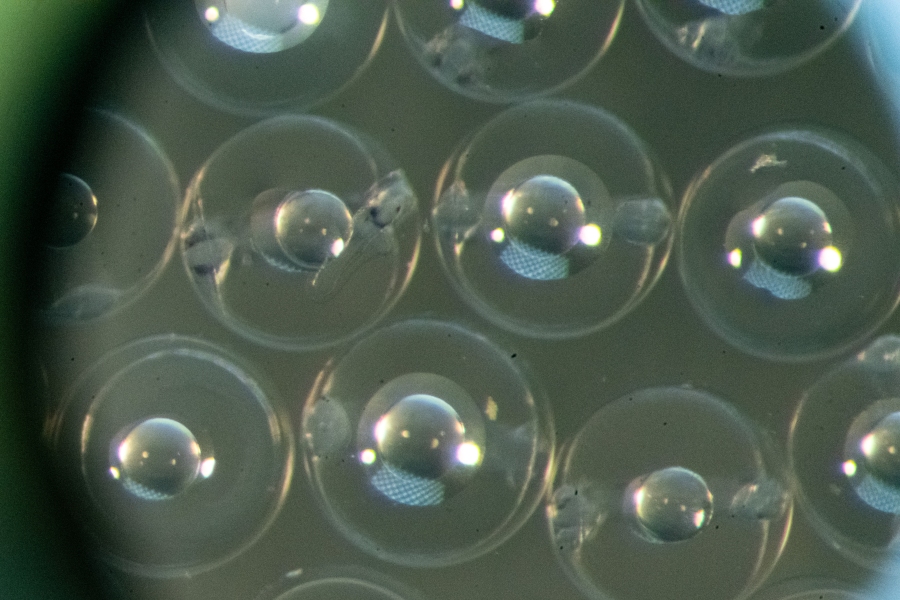

“What influences the species’ early life stages is not very well understood. We measured the buoyancy of hoki eggs as they developed. It was found that eggs were more buoyant immediately after spawning and again after hatching. These measurements can be used to populate drift models with real information to determine where early stage larval fish end up and identify constraints or bottlenecks that impact early life history”.

Hoki eggs were collected using conical, fine mesh plankton nets. Buoyancy experiments were then carried out in a temperature-controlled laboratory, set to 10˚ C, using columns populated with up to 100 eggs.

At the same time, midwater trawls were used to catch small fish that were suspected to be eating hoki eggs. Fisheries scientist Pablo Escobar-Flores was surprised by the results:

“Hoki eggs were detected in the stomachs of over half the lanternfish (Lampanyctodes hectoris) that we looked at, with one individual containing 49 eggs!”

This highlights the role of lanternfish not only as one of the main food items of hoki but also as consumer of their predator’s eggs.

Underwater images of adult spawning hoki were also taken using a range of camera systems. These images will be used to measure the density and orientation of hoki within schools to improve acoustic estimates of hoki abundance.

The Cook Strait research voyage was jointly funded by Ministry for Business Innovation and Employment, NIWA and Fisheries New Zealand. Learn more about how NIWA provides scientific advice to Fisheries New Zealand.