Scientists mapping the Hauraki Gulf seafloor have discovered huge colonies of tubeworms up to 1.5 metres high and collectively covering hundreds of metres providing vital habitats for plants and animals.

This is the first time the tubeworms (species Galeolaria hystrix) - invertebrates that anchor themselves to the sea floor – have been found north of the Marlborough Sounds as large colonies, although NIWA marine ecologist Dr Mark Morrison says they are likely to have always been there.

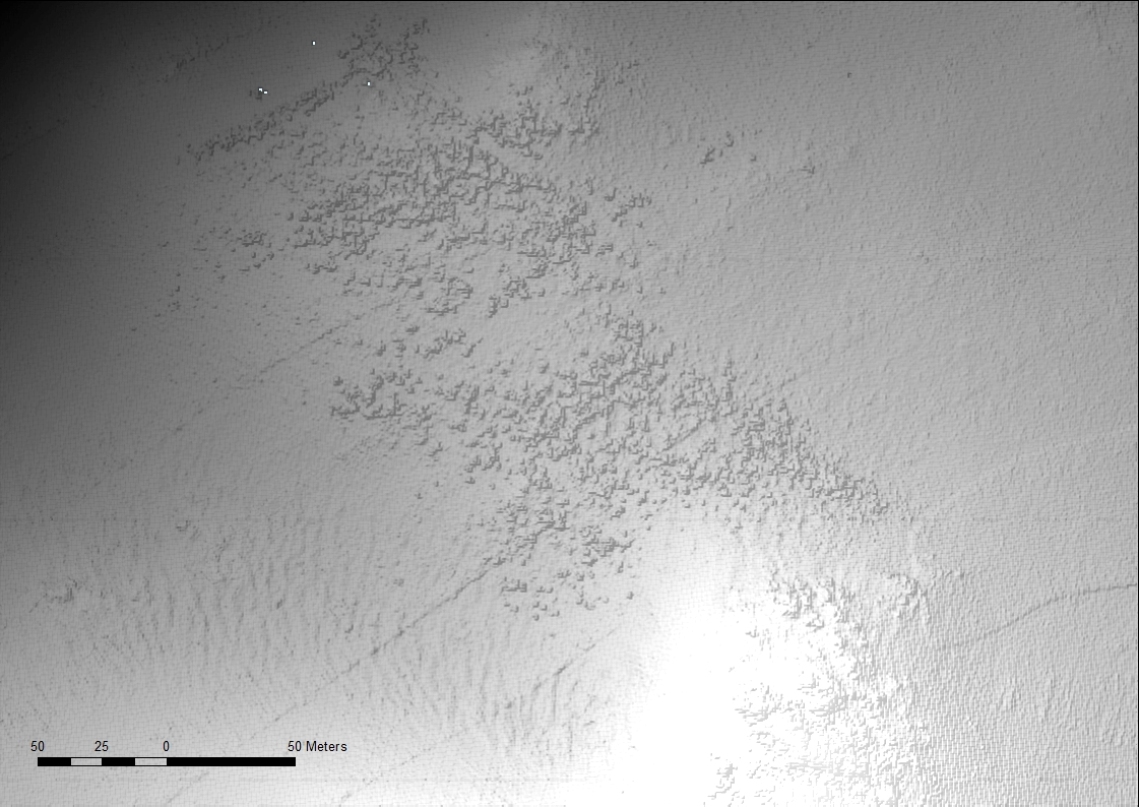

The tubeworm colonies in the Gulf appeared as large, mysterious bumps on a computer screen during analysis of a multibeam mapping project being carried out by NIWA. This type of mapping uses multibeam echo sounders to emit a fan of sound beams to the seafloor to scan detailed sections of the seabed.

“We had a suspicion there was something out there when we had a net ripped to pieces during a snapper sampling survey a few years ago, and what remained of the net was full of tubeworms. This time we saw all these bumps from the multibeam – hundreds of them – but couldn’t figure out what they were.”

Dr Morrison sent out a team of researchers to “ground-truth” the findings by videoing the areas where the bumps had been seen. It was then they discovered field after field of tubeworms.

“They’re quite solid because they’re made out of many colonies of worms growing on each other – generation after generation – so when you get to the middle it’s like a whole lot of worm tubes fused together. They secrete calcium carbonate and the tubes fuse together so you’ve got these huge masses and as they die new ones grow on top.”

Dr Morrison said the tubeworm fields occur in depths between 12 to 22 metres and have so far been found around Pakatoa Island on the east side of Waiheke Island, and around Motumorirau Island, north of Coromandel Harbour.

The colonies shelter fish such as bastard red cod, cusk fish and rockfish. “There is also heaps of stuff growing on them like red algae, sponges, sea squirts, hydroids, bryozoans, and feathery brittlestars. It’s what we call a biogenic reef - a living reef - with fish using it for cover and foraging,” Dr Morrison said.

He said part of the value of the tubeworm fields is the structure it provides for other animals and plants to use.

“I’m sure such biogenic reefs were once a lot more common before sedimentation, trawling, and dredging damaged them. We tend to find them next to islands or on slopes that are probably quite hard to fish. They are also away from some of the worst sedimentation in the Gulf and more out towards open water and I suspect, based on their similar topography and environmental conditions, that there are more at the Happy Jacks/Motukawao islands.”

Dr Morrison said it was exciting to have found such unexpected diverse habitats in the Hauraki Gulf, which has undergone large scale environmental degradation.

The multibeam sonar mapping was able to be carried out due to funding by Foundation North’s GIFT Fund, which encourages breakthrough insights and solutions to environmental issues in the Hauraki Gulf. Other funding was also provided by Auckland Council, Waikato Regional Council and NIWA Strategic Science Investment Fund. In addition, some Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) data were also used. The subsequent video ground-truthing was funded through the MBIE Research Programme Juvenile fish habitat bottlenecks.

“All up the tubeworm fields we found totalled together to more than a square kilometre – that’s not a lot in the context of the Gulf overall but it’s still pretty exciting because small places can have quite a disproportionate value.”

Dr Morrison said there was potential for the fields to be classified as significant ecological areas that would help protect them.

“These colonies add a lot of value to the Gulf ecosystem and it’s important that the habitat isn’t destroyed.”

More research is to be carried out to determine the tubeworm fields’ relative importance as fish nurseries, in particular for snapper.