Scientists have discovered an abrupt increase in the uptake of atmospheric carbon dioxide by the land biosphere (which comprises all of the planet's plant and animal ecosystems) since1988. Without this natural increase in uptake, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would probably have increased even more rapidly over the last two decades.

These new results have been reported in a recent paper in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, written by an international team of scientists including NIWA atmospheric scientist Dr Sara Mikaloff-Fletcher.

"The scientific community has known for a long time that the land biosphere takes up CO2. What's new about this study is that we have discovered an abrupt shift towards more uptake by the land biosphere since 1988. Our team applied mathematical techniques that haven't been widely used in this field to detect the shift," says Dr Mikaloff-Fletcher.

The increase in uptake is a big number - about one billion tonnes of carbon per year. To put it into context, that is over 10 per cent of the global fossil fuel emissions for 2010.

"While the increase was shown to be significant, the physical processes driving it remain a mystery. It poses big questions for us. What caused this shift? What can it tell us about how land's ability to take up CO2 is going to change in the future, and the sensitivity of the land carbon sink to climate? How is that going to feed back into climate conditions in the future?" says Dr Mikaloff-Fletcher.

Ongoing work with land models and atmospheric data will be used to explore these questions.

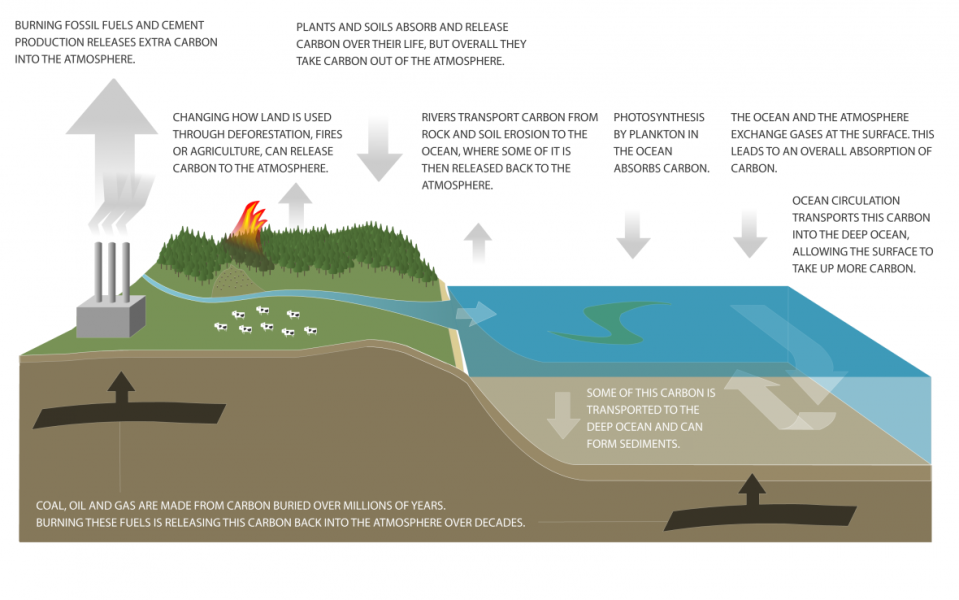

Between 1958 and the present, over half of the emissions of CO2 from human activities have been absorbed by the land biosphere and the oceans. But these natural sinks can be difficult to quantify directly.

The scientists take carbon emissions from human activities, subtract what is retained in the atmosphere and what the oceans take up, which leaves the land component.

The amount of CO2 that remains in the atmosphere is the best known part of the global carbon cycle and is calculated from a global network of stations that measure greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, such as the NIWA sites at Baring Head and Lauder in New Zealand and Arrival Heights in Antarctica.

"We also know a lot about the fossil fuel emissions from fossil fuel burning statistics and data on energy production, consumption, and trade. These emissions estimates are available at the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center in the U.S." says Dr Mikaloff-Fletcher. This study estimated the land sink for CO2 from 1958. An international team of researchers at Princeton University (USA), NIWA (New Zealand), and the University of Missouri (USA) noticed an abrupt shift in the land sink in 1988, towards greater land uptake. They applied a suite of statistical techniques to objectively determine the timing, size, and statistical significance of this shift. They explored whether it could be explained by volcanic eruptions or the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) – it can't.

"My area of research is to answer questions about how much carbon is being taken up by the land and how much by the ocean, how the uptake varies with time, and what is driving this variability. If you have carbon being taken up by plants and then you change the climate, you are going to change temperature and precipitation patterns and other factors. This is going to affect the biosphere's ability to take up carbon," says Dr Mikaloff-Fletcher.

Current climate change scenarios are based on observed levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, so they already include the effects of land and ocean carbon sinks. What is relevant to these climate change scenarios is the question of whether this increase in carbon uptake by land is temporary. If it is temporary, reducing CO2 levels may get even harder in the future.

This research was funded by Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies, the Carbon Mitigation Initiative with support from BP, the Cooperative Institute for Climate Science, and the New Zealand Ministry of Science and Innovation. The work is published in the paper "Identification and characterization of abrupt changes in the land uptake of carbon," by Claudie Beaulieu, Jorge Sarmiento, Sara E. Mikaloff Fletcher, Jie Chen, and David Medvigy available at https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2010GB004024.