Since the end of June, a barge has been stationed just off Wellington’s Miramar Peninsula drilling into the seabed to find an alternative water source for the city. Wellington needs it in case there’s a large earthquake and existing water supply routes are damaged. But why go to sea to find fresh water? NIWA marine geologist Dr Scott Nodder explains.

What’s out there?

Aquifers are common sources of water around New Zealand and typically comprise buried layers of gravels deposited originally by rivers that are capable of holding and storing groundwater. These gravel layers are ‘confined’ by overlying fine-grained sediments that are often predominantly muddy deposits deposited in marine or land environments.

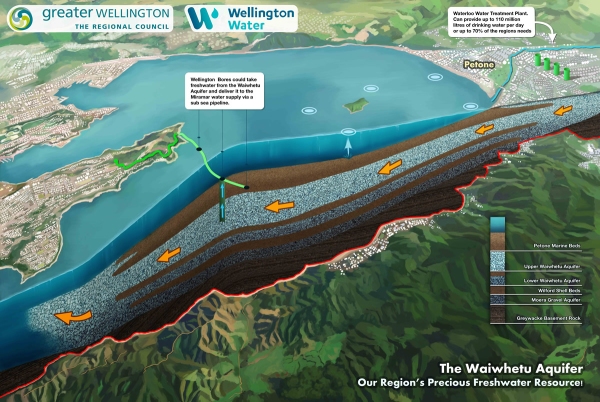

There are two aquifers beneath Wellington Harbour: the Waiwhetu Aquifer and the Moera Aquifer. Along the Petone foreshore, the Waiwhetu Gravels are 20-30 metres below ground level and the Moera Gravels are at 100-160 metres down. Last year, NIWA surveyed the Wellington Harbour/Te Whanganui a Tara for Wellington Water Ltd to image the geological layers that mark the top and bottom of the Waiwhetu Aquifer and found it extends across the Harbour to Miramar Peninsula/Te Motu Kairangi. Beneath the harbour the aquifer is buried under a 30-40m-thick layer of mud or marine origin, which acts to ‘confine’ the aquifer and pressurise the water contained in the gravels.

The Waiwhetu Aquifer provides more than 40 per cent of the freshwater demands of Wellington City and environs, including Porirua and Lower Hutt cities. This extraction from the aquifer can rise to as much as 70 per cent of the demand in summer when river levels are low.

What’s an aquifer and how does it work?

An aquifer is a saturated underground layer of permeable rock, gravel, sand or silt through which water can move easily – they store huge amounts of freshwater that can be accessed via a bore.

Water in aquifers is derived from rivers and to a lesser extent rainfall. Groundwater levels are influenced by factors such as river stage, rainfall recharge and extraction rates. Tidal and barometric pressure variations also affect groundwater levels in confined aquifers. Discharge from the Waiwhetu Aquifer occurs beneath the harbour and has formed large depressions in the seafloor off Point Howard (Seaview), the Hutt River/Te Awa Kairangi mouth and Somes Island/Matiu.

How do you know where the best place to drill is?

NIWA has mapped the extent of the upper part of the Waiwhetu Aquifer gravels across the harbour from where it is known to intersect the borehole off Somes Island/Matiu. We have used shallow geophysical techniques, involving sound sources and hydrophones, towed behind survey vessels, to generate an image of the aquifer beneath the seafloor. However, the only way to be absolutely sure the aquifer is where we have mapped it is to drill to retrieve and test the fresh water within the aquifer.

If there was a significant earthquake that disrupted the existing water supply, wouldn’t the aquifer be affected as well?

Yes, there is potential for this to occur, as was the case in Christchurch after the recent earthquakes there. The borehole drilling, however, will provide additional resilience to the infrastructure required for getting water to areas of Wellington City that may be potentially disrupted or damaged by a local earthquake.

You will be examining the core samples of the seabed brought up by the drilling rig – what will they tell you?

The geological samples from the cores will be described and collected by geologists from Stantec MWH and GNS Science. This will provide new information about the geological history of Wellington Harbour/Te Whanganui a Tara and the conditions of the aquifer and its confining layers, which will improve our understanding about the physical and hydraulic characteristics of the Waiwhetu Aquifer (i.e., size and density of sediment grains and water pressures in the aquifer). The information will find use in studies investigating the climatic, sea-level and tectonic evolution of the area. The water from the aquifer will also be chemically tested and monitored to determine if it is suitable as a drinking water source. NIWA is providing technical skills in this monitoring.

[This feature appeared in Water & Atmosphere 19]