A team of scientists aboard NIWA’s deepwater research vessel Tangaroa returned to Wellington with new knowledge about methane ‘leaking’ into the atmosphere.

The 11-strong science team led by marine geologist Dr Joshu Mountjoy has been investigating an area off the east coast of the North Island near Gisborne where 99 seabed gas flares were identified for the first time in 2014.

“We wanted to find out whether methane is getting through the water column to the ocean’s surface and into the atmosphere – if so, how much – and determine what contribution it’s making to global greenhouse gas,” said Dr Mountjoy.

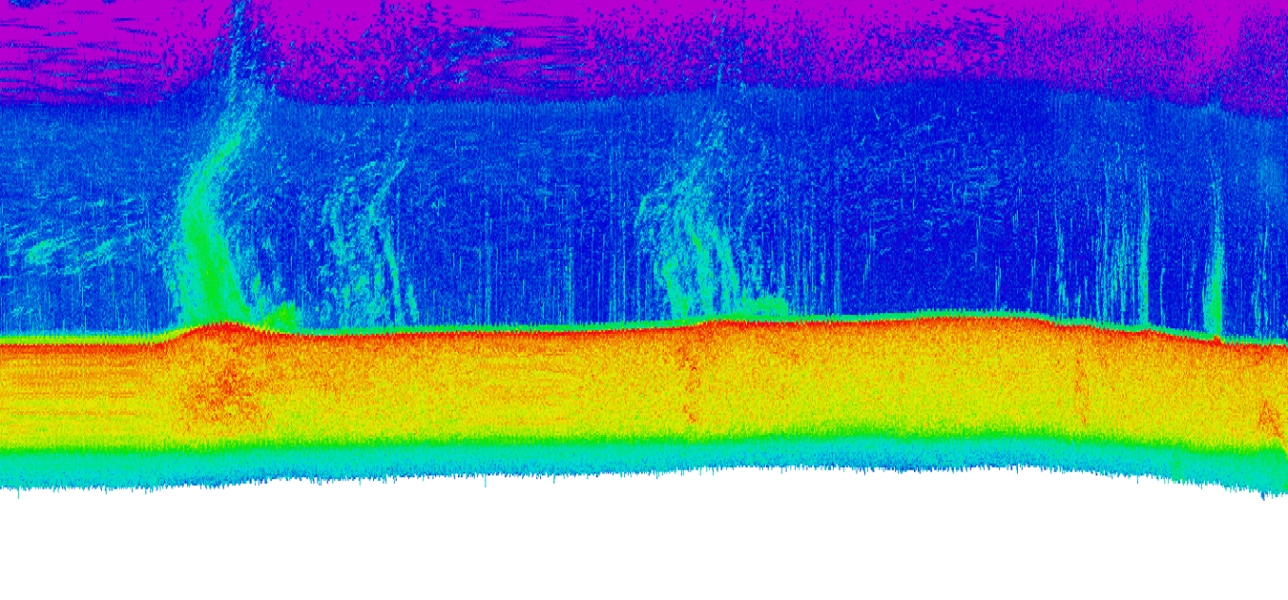

The first objective of the voyage was to remap gas flares in the area in fine detail, using a range of acoustic techniques. Surprisingly the team discovered that every area of carbonate rock and every fault seen on the seafloor was expelling gas. In total they calculated that there are near to 766 individual gas flares within the area.

By sampling methane gas within the ocean and collecting photographs and graphic imagery with NIWA’s deep-towed imaging system, Dr Mountjoy and marine ecologist Dr Ashley Rowden were also able to build a picture of the fate of the gas flares, and acquire a deeper understanding of the ecology at the relatively shallow seep sites.

“We have recorded video footage showing columns of bubbles streaming out of the sea bed,” said Dr Mountjoy.

“Preliminary indications are that methane is reaching the ocean surface – this is the first time this has been measured in New Zealand,” he said. “However, to understand how much methane, and then what this means for atmospheric contributions, will require detailed analysis of the data.”

The biological survey of the gas flares zone has secured a major advance for science, with observations suggesting that chemoautophic species (those that depend for food on a symbiosis with bacteria that use the methane) can occur at relatively shallow depths,

Dr Rowden says that this means the scientific understanding of the life that inhabits the area of these gas seeps needs to be re-evaluated, and a new model formulated.”

Background

The network of gas seeps off the Poverty Bay coast was discovered during a research voyage on the Tangaroa last year. Some of the seeps are venting from the seabed in flares up to 250m high. The discovery of this high concentration of gas flares in shallow water depths – 100m-300m – on an active tectonic subduction zone is unique. Gas seeps are usually much deeper, at 600m-1000m below the surface.

Dr Mountjoy says the team identified methane gas in the sediment and in the ocean, and vast areas of methane hydrates – ice-like frozen methane – below the seafloor.

This Autumn’s research voyage [April 23 to May 1] continues the work of an international project focusing on the interactions between gas hydrates and slow-moving landslides called SCHLIP – Submarine Clathrate Hydrate Landslide Imaging Project.

Tangaroa’s voyage, and its role in the collection of scientific data is being filmed by a visiting French fourth-year arts student, Pauline Martinez Le Ninan, who is studying the spirit of science, including ocean geology.