An ambitious scientific expedition involving 30 scientists from around the world leaves Perth next week bound for the East Coast of the North Island.

The expedition, jointly led by NIWA and the University of Auckland and funded by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), is the first of two aboard the US National Science Foundation-operated scientific drilling research vessel, JOIDES Resolution. The scientists will study the Hikurangi subduction zone to find out more about New Zealand’s largest earthquake and tsunami hazard.

The Hikurangi subduction zone is part of the Pacific ring of fire where the Pacific tectonic plate dives beneath the Australian plate. Scientists believe the zone is capable of generating earthquakes of more than Magnitude 8.

The scientists will spend six weeks, including Christmas and New Year, at sea between 30 and 100km off the coast of Gisborne, studying two main features of the area: slow-slip events and submarine landslides. This will help to reveal the causes of these phenomena and improve understanding of the risk that the plate boundary poses to communities along the East Coast and rest of the country.

Slow slip events on subduction faults – a type of creeping behaviour – are bursts of movement on the fault that last from weeks to months rather than minutes as in large earthquakes. Scientists only learned of their existence about 15 years ago, and are trying to solve the mystery of how they happen. They have been described as the most significant seismological discovery in recent years.

Expedition co-leader and NIWA marine geologist Dr Philip Barnes says while slow slip events have been recorded around the world, the New Zealand examples in the northern part of the Hikurangi subduction zone are special because they happen in relatively shallow depths beneath the seafloor where data can be collected to help reveal how they work.

“Right now, we can only speculate about what’s driving them. For a slow slip event to occur you require the fault to move a little and slowly, without the movement advancing into a normal earthquake rupture.

“Since their discovery scientists have come to understand that there is a whole continuum of seismological processes between constant creep on a fault and big earthquakes, and slow slips are one of those,” Dr Barnes said.

Understanding the relationship between slow slip events and earthquakes is an important aspect of this work. Last year’s Kaikoura earthquake triggered a large slow slip event offshore the east coast covering an area of more than 15,000 square km. The east coast triggered slow slip event initiated in the region of the planned IODP drilling, so the results from the expedition should shed new light on why this occurred.

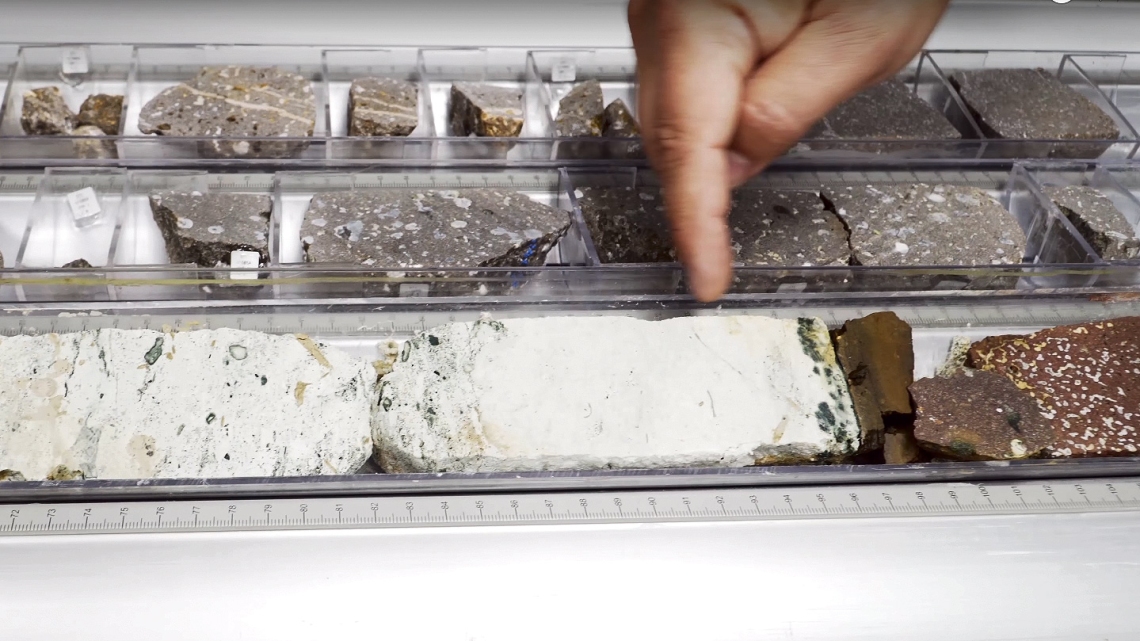

The scientists will collect drilling data up to 1200m beneath the seafloor at three sites that range in water depth from about 1000 m to 3500m. During the drilling, instruments will record physical information about the rock types that are thought to host the subduction fault, and the properties of faults that splay from it to reach the seafloor.

The second focus of research on this expedition will study the underwater Tuahine landslides, led by Dr Ingo Pecher of the University of Auckland. Dr Pecher says scientists want to learn about the relationship between gas hydrate – a solid ice-like substance formed under the seafloor where gases are trapped in water – and creeping.

“Scientists have thought for more than 30 years that this ice-like substance stiffens the seafloor, whereas its dissociation, i.e., melting may lead to submarine landslides.

“Recent evidence discovered east of Gisborne however, suggests that hydrate itself may be responsible for creeping of submarine landslides. We plan to study how gas hydrates may cause such slow deformation,” Dr Pecher said.

On the second Hikurangi expedition, which leaves in early March, core samples will be taken and borehole observatory instruments placed in two of the drill holes that will continue to collect data, for a number of years. The March expedition will be led by Dr. Laura Wallace of GNS Science and Professor Demian Saffer of Pennsylvania State University.

Dr Barnes will also be on board the second voyage and says both expeditions represent a massive financial investment in New Zealand science by the international IODP consortium.

“This region, offshore of Gisborne, has been recognised by the international science community as the best location on earth to use available ocean drilling technology to improve understanding of what causes slow slip events.

“Together the data and seafloor observatories will contribute a great deal to understanding fundamental subduction fault processes. Hopefully they will also underpin future improvements in hazard assessment for New Zealand, leading to a more resilient society.”

All data collected will be publicly available from mid-2019.

New Zealand participates in IODP through a consortium of research organisations and universities in Australia and New Zealand, including GNS Science, NIWA, University of Auckland, Victoria University of Wellington, and University of Otago. The Australia and New Zealand IODP Consortium (ANZIC) is supporting participation of New Zealand scientists and outreach officers on both expeditions.

For more information see:

Creeping gas hydrate slides and Hikurangi LWD (logging while drilling)