Problem

Sharks are vulnerable to overfishing because they reproduce slowly, often take a long time to grow to adulthood, and when unfished can live for many years. Surface longline fisheries, which target mainly tunas and swordfish in oceanic waters throughout the world, catch many pelagic (open-ocean) sharks.

The commonest shark species taken as bycatch are blue, silky, shortfin mako, porbeagle, oceanic whitetip and thresher sharks. Most pelagic shark species fall near the middle of the shark productivity scale, and there is concern that catching too many of them could lead to population depletion.

Pelagic sharks and the main fisheries that catch them are wide ranging, often encompassing entire ocean basins. To assess the status of shark stocks, and to manage them, multiple nations must collect and analyse a large amount of data from a vast area. Research and management must therefore be co-ordinated on an international scale, a task being undertaken by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs). One RFMO, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) has led the way in developing large-scale shark population status assessments.

Unfortunately, the data available on pelagic sharks are generally limited and of low quality, so in many cases we cannot use the stock assessment methods that are normally used for target species. This has led to the need to develop new and innovative approaches for assessing the status of data-poor species.

Solution

WCPFC, in partnership with the Common Oceans ABNJ Tuna Project, contracted NIWA to develop methods for assessing the Pacific population of bigeye thresher shark (Alopias superciliosus), and the Southern Hemisphere population of porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus). NIWA developed a new method for spatially-explicit, quantitative, sustainability risk assessment. The method estimates risk as the ratio of current fishing mortality and a maximum impact sustainable threshold (MIST), which is based on population productivity. A key element of the method is to estimate a probability distribution for the risk.

Result

Pacific Ocean bigeye thresher shark risk assessment

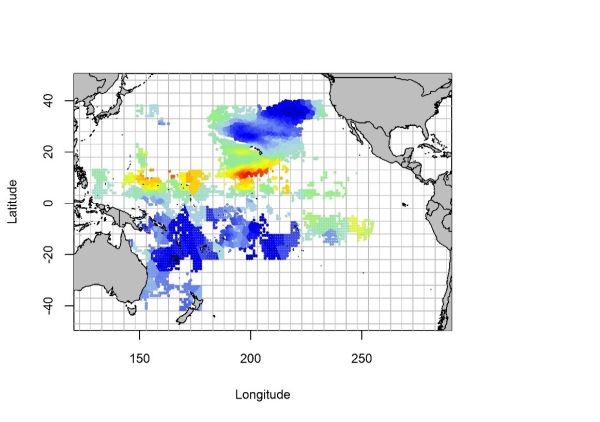

Earlier studies indicated that bigeye thresher shark is vulnerable to exploitation owing to limited productivity, even at relatively low levels of fishing mortality. Our estimates suggest that total fishing mortalities from pelagic longline fisheries in the Pacific since 2000 have been low (< 5%), but may still be greater than the population can sustain. For a variety of scenarios (ranging from more to less conservative MIST values, and using different assumptions about the proportion of discarded sharks that survive), the probability that the MIST was exceeded ranged from 0.20 to 0.77.

Areas with the highest fishing mortality overlapped with the region of higher relative abundance of thresher sharks, corresponding to a narrow band across the North Pacific (approximately 10–15° N and 150° E–140° W). We identified a hotspot southwest of Hawaii (at 161–167 °W). Management responses to protect such hotspots may include spatial closures with or without seasonal restrictions, or move-on measures (e.g. if shark catches exceed a certain level, vessels must move to another area). These results will help managers to develop more focused management options for the species in the Pacific.

Southern Hemisphere porbeagle shark risk assessment

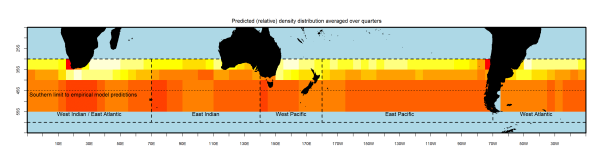

Porbeagle sharks are an active cold-temperate pelagic species related to white sharks and mako sharks. They are found in both the north Atlantic and the Southern Ocean, but the southern stock is genetically distinct, has smaller body size, and lives longer. The Southern Hemisphere population structure of porbeagle sharks is not well understood, and we considered it unlikely that the population comprises a single well-mixed stock for management purposes.

We subdivided the assessment into five subpopulations by longitude:

- Western Atlantic Ocean;

- Eastern Atlantic/Western Indian Ocean;

- Eastern Indian Ocean;

- Western Pacific Ocean; and

- Eastern Pacific Ocean.

We applied different assessment methods by region, depending on data availability and quality.

Annual fishing mortalities were greatest in the Eastern Atlantic/Western Indian Ocean, slightly lower in the Eastern Indian Ocean, and lowest in the Western Pacific Ocean. The risk assessment indicated low fishing mortality rates in the three regions comprising the assessment area, and low risk from commercial pelagic longline fisheries to porbeagle shark over the whole Southern Hemisphere. The fishing mortality was less than 9–18% of the MIST in all years assessed (1992–2014) and fell to half that level in more recent years. These results are consistent with the trends observed in other catch rate indicators, which in most cases show stable or increasing catch rates.

Because of a lack of suitable data, our risk assessment assumed that population density from 45 to 55oS is the same as at 40 to 45oS, and that density south of 55oS is zero. We have evidence from fisheries and surveys that porbeagles occur south of 45oS, but we do not have longline observer data with which to estimate density. This is an important assumption, because it implies that the low fishing effort south of 45oS provides a refuge from fishing mortality for the population. Biological data, and estimated relationships between size and sea surface temperature, suggest that a high proportion of the adult population occurs at these latitudes.

These results will help national and international fishery managers to develop more focused management for the species throughout the Southern Ocean. A key recommendation from this project is to continue to collect and analyse indicators from observer data.